by Katy Rubin

Feature image credit: Theatre of the Oppressed NYC

How do we, as citizens, begin to participate in designing and changing policy, before we are able to articulate the relationship between what we experience in our daily lives, and the laws, rules and designs that impact those experiences? I am inspired by the frame of “citizen as a verb” used by Baratunde Thurston on his blog “How to Citizen,” in which “citizen” is not a noun defined by nationalities or passports, but an active practice, open to all residents. To citizen, like any physical or mental challenge, we build skills with continued practice. Legislative Theatre offers one such exercise programme, which is accessible (and fun!) for both democracy newbies and seasoned policymakers.

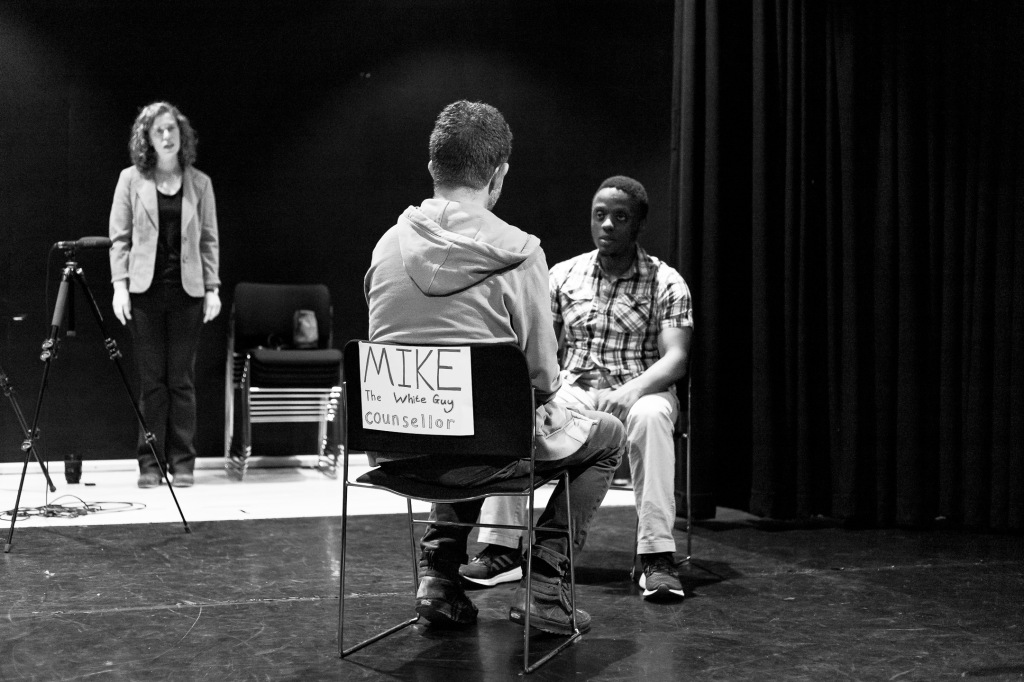

Three decades ago, Theatre of the Oppressed creator and activist-turned-city councillor Augusto Boal brought a community theatre performance into Rio de Janeiro’s city council chambers, inviting the public and his fellow councillors to test out changes to local legislation by improvising in the scene. That was the birth of the Legislative Theatre methodology, which is now practised around the world, from New York City to Colombia, from London to India — creative, radical, participatory democracy, built on a foundation of the ethics and techniques of Theatre and Pedagogy of the Oppressed. In Legislative Theatre (LT), audiences and policymakers watch a play based on the community actors’ experiences of oppressive policies and practices. Then, audiences act onstage to rehearse ways to confront the problems presented and test new policies in real time. This testing leads actors and audiences to propose ideas for new policies to address the problems, working together with advocates and government representatives. Finally, audience members vote on their priorities, and decision-makers commit to immediate actions.

From 2013-2018, I worked to develop this practice as executive director of Theatre of the Oppressed NYC, and since 2019, I’ve been collaborating with local governments to implement and amplify LT across the UK. Various concrete policy wins have followed directly from LT processes in the UK and the US, including the co-creation of the first Greater Manchester Homelessness Prevention Strategy (2021-2026), which won the International Observatory of Participatory Democracy 2022 Award for Best Practice in Citizen Participation. However, while LT and other participatory democracy methodologies should, and do, result in more equitable and effective policies and budgets, the civic activation and consciousness-raising that grow from these processes can have lasting power.

In an LT process, community members begin by playing games that reveal, physically and emotionally, the way that rules are embedded inside us and outside in society. These games lead to discussions about the rules we are forced to follow daily, and how they might stop us from accessing our rights and living with dignity. When we talk about rules, we’re equally concerned with the very local to the international. We must examine rules we make or follow in our homes and families alongside the rules we experience in the school, the hospital, the parliament. These discussions lead to stories, which lead to scenes, which become tools for framing a policy problem. Once the actors have framed the problem in this human-centred way, the audience can understand it both emotionally and analytically, and only then are we ready to imagine and test new alternatives with the broader public.

Image credits: Ingrid Turner and Steve Hosey

In Newcastle, as part of a recent series of LT practitioner training, a group started a chant, dancing around the room: “Everything’s a Rule!” They marvelled aloud at their brand-new lens: now they saw rules everywhere! One woman was driving to the workshop and heard a radio advertisement encouraging listeners to upgrade to insulated windows. She started to think about rising fuel prices, and how expensive it had become to heat her home. Who made the decision that this problem was hers alone? Why weren’t there subsidies or other interventions readily available to help residents insulate their homes? These questions could lead her and the group to further research about how the lack of infrastructure and investment in climate solutions lead to unsafe living conditions, which would form the narrative for a play.

In the rehearsals for Greater Manchester’s Homelessness Prevention Strategy project, a community actor told a story of being discharged from short-term drug and alcohol rehab without anywhere to go, when he didn’t feel that his treatment was complete; he felt dismissed by the staff person handling his case. The LT process asks us to resist the instinct to blame the front-line worker. A common solution in these instances is empathy or customer service training for staff, which keeps the focus on interpersonal relationships. Instead, we can question the rules of the rehab, the funding and commissioning process of the council, and beyond. Who sets treatment limits? Are patients consulted on the time of their discharge? Are there rules in place determining the support required before someone who may be facing homelessness is released? How much do these centres cost, and who makes the funding decisions? What messages do we receive, in school, or on TV, that housing insecurity is a personal failure, and who tells those stories? (Margaret Thatcher, for one!)

In these exercises, we begin to “zoom out” and investigate who made the rules, why they made them, where they are made, and what hidden interests might lie behind them. This investigation includes research and external expertise, but it starts with our own knowledge. We already have much of the information we need: it’s a collective, embodied process of understanding where our shared experiences intersect with the rules.

Legislative Theatre can offer an accessible, fun, and inclusive approach for citizens – in the collective and expansive definition of the word – to explore those connections themselves, and to understand them intellectually, physically and emotionally. As part of an ecology of participatory processes, Legislative Theatre allows citizens to connect and call out policies that widen inequality. It helps communities generate new alternatives with the creativity and imagination they demand, and inject much-needed joy into the process.

Katy Rubin is a Legislative Theatre practitioner and civic strategist based in the UK, collaborating with local councils, advocacy organisations and community groups to co-create policies and practices that are human-centred, equitable, innovative and effective. Currently working on housing and homelessness, food poverty, mental health, the climate crisis, and cultural policy, she is passionate about creative policy change that moves the needle towards equity. Katy is also a Senior Fellow with People Powered: Global Hub for Participatory Democracy; Associate with Shared Future CIC; and 2023-24 Atlantic Fellow for Social and Economic Equity at London School of Economics.